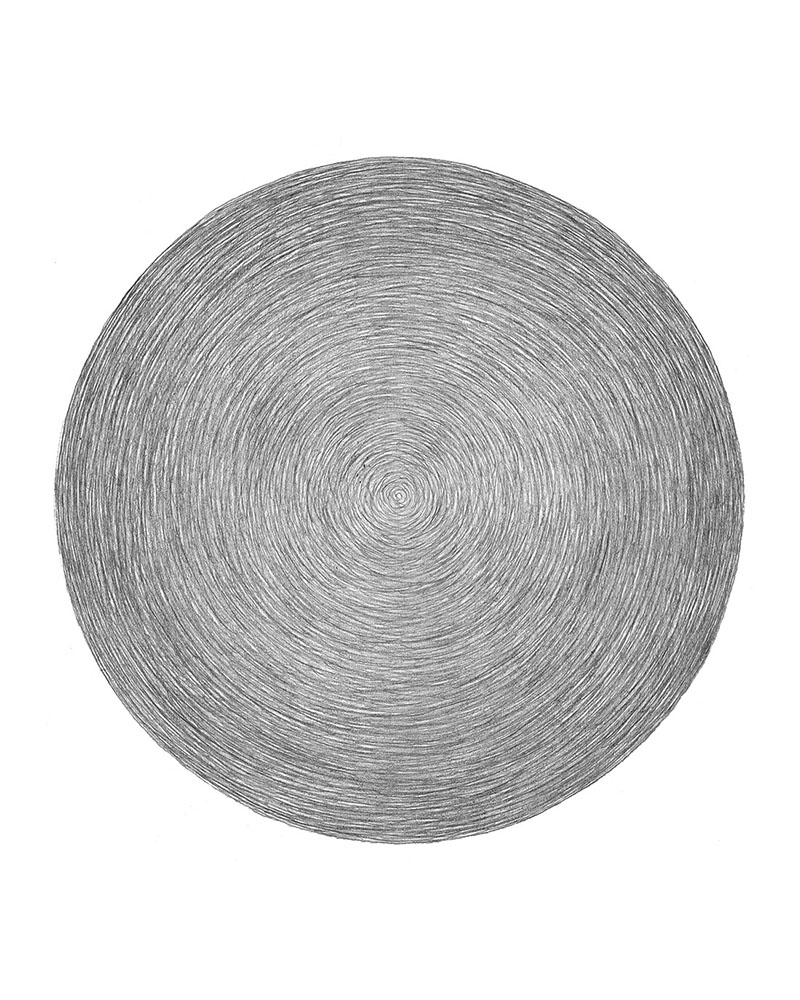

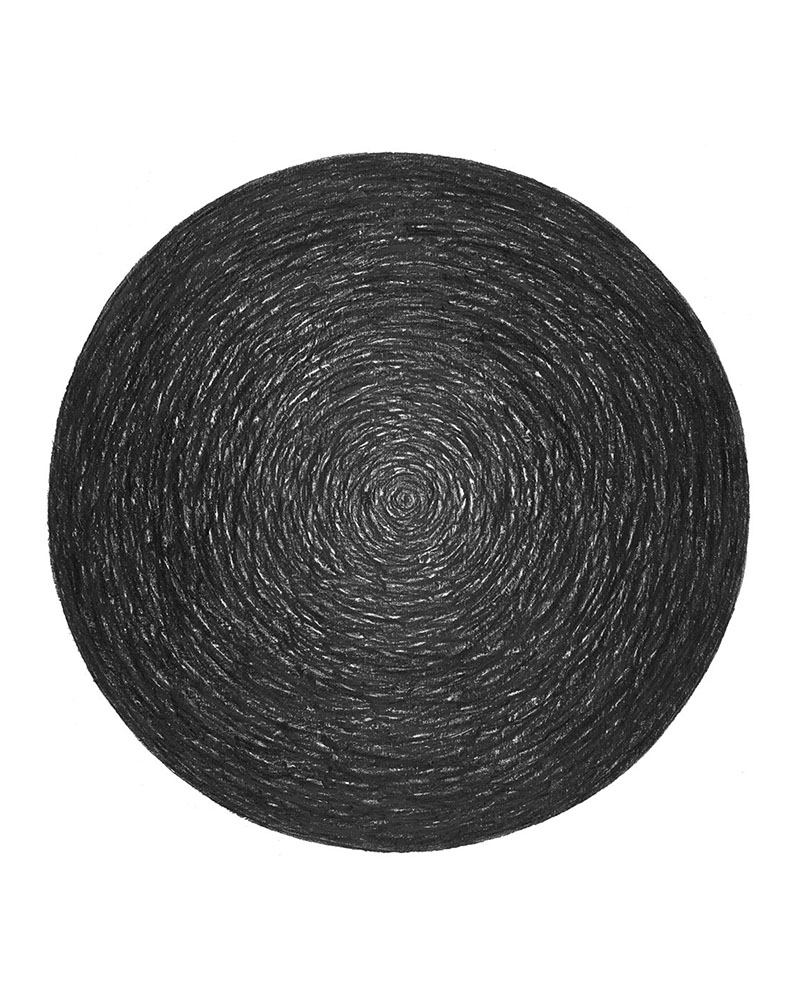

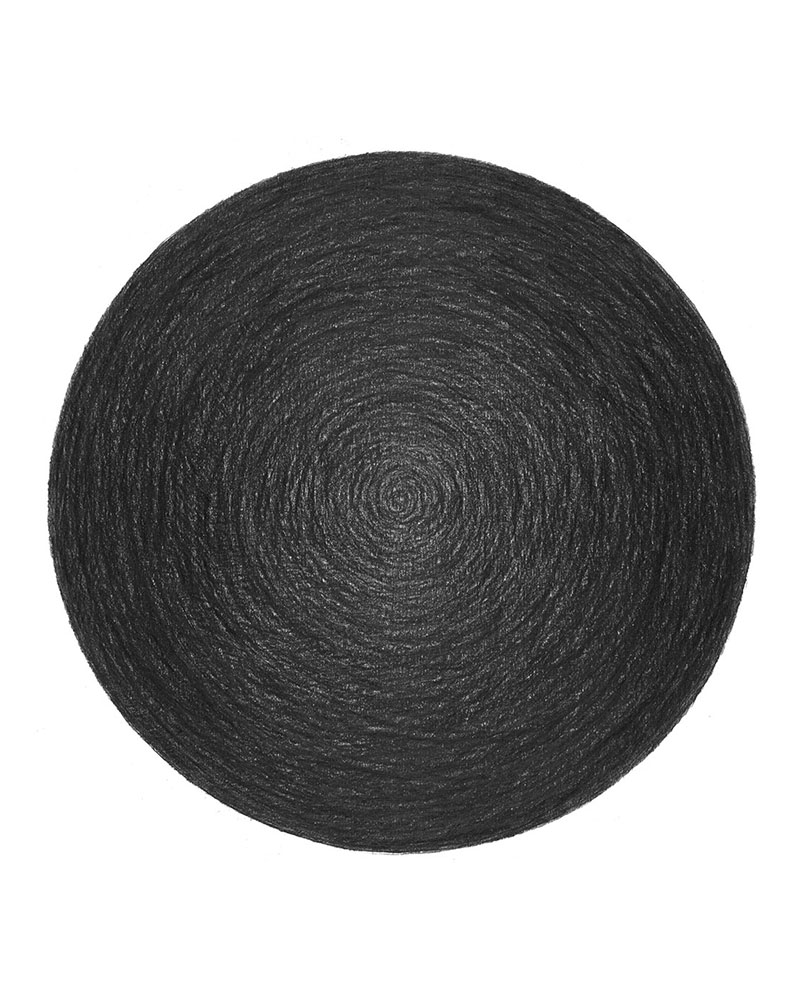

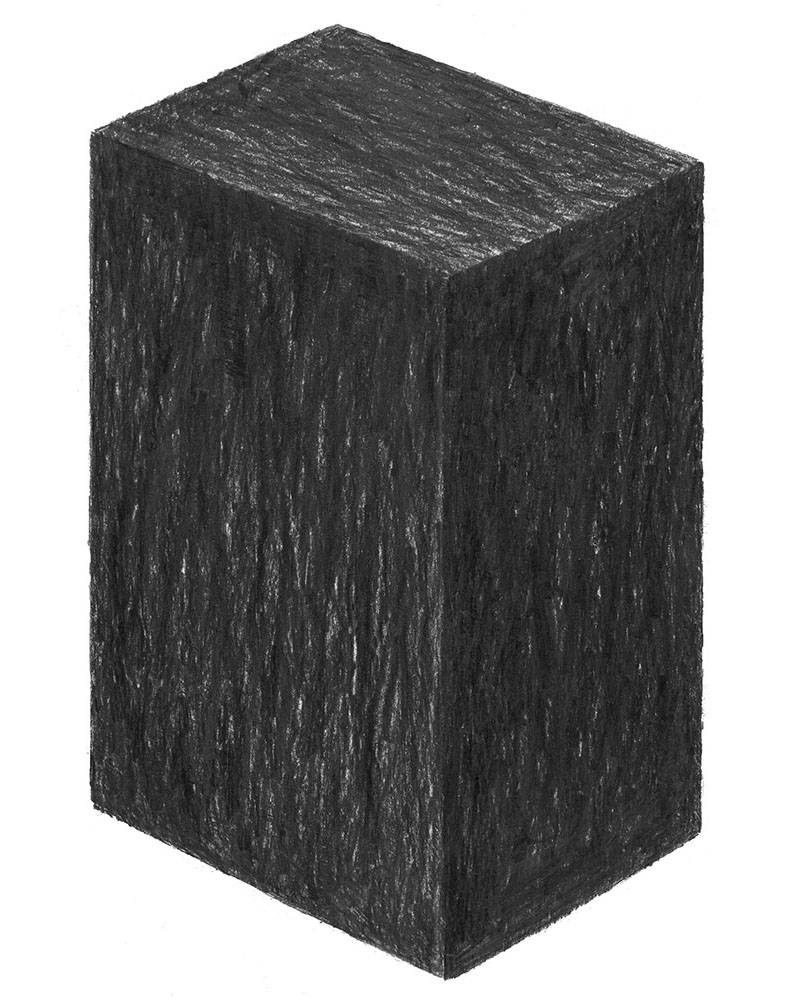

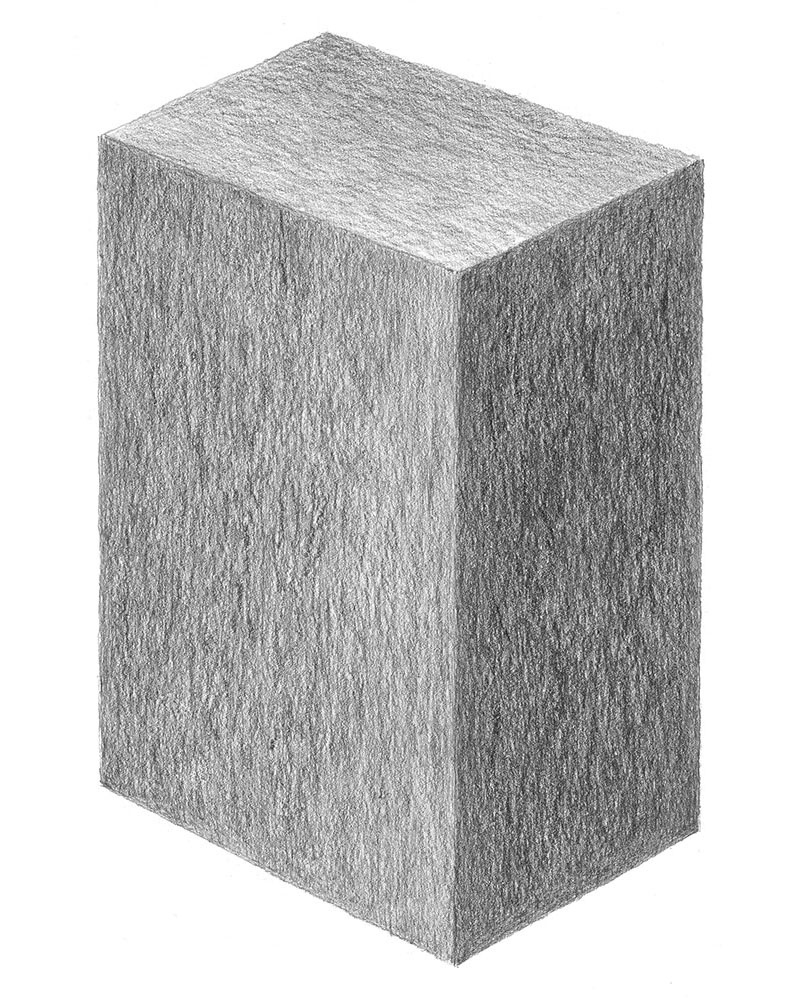

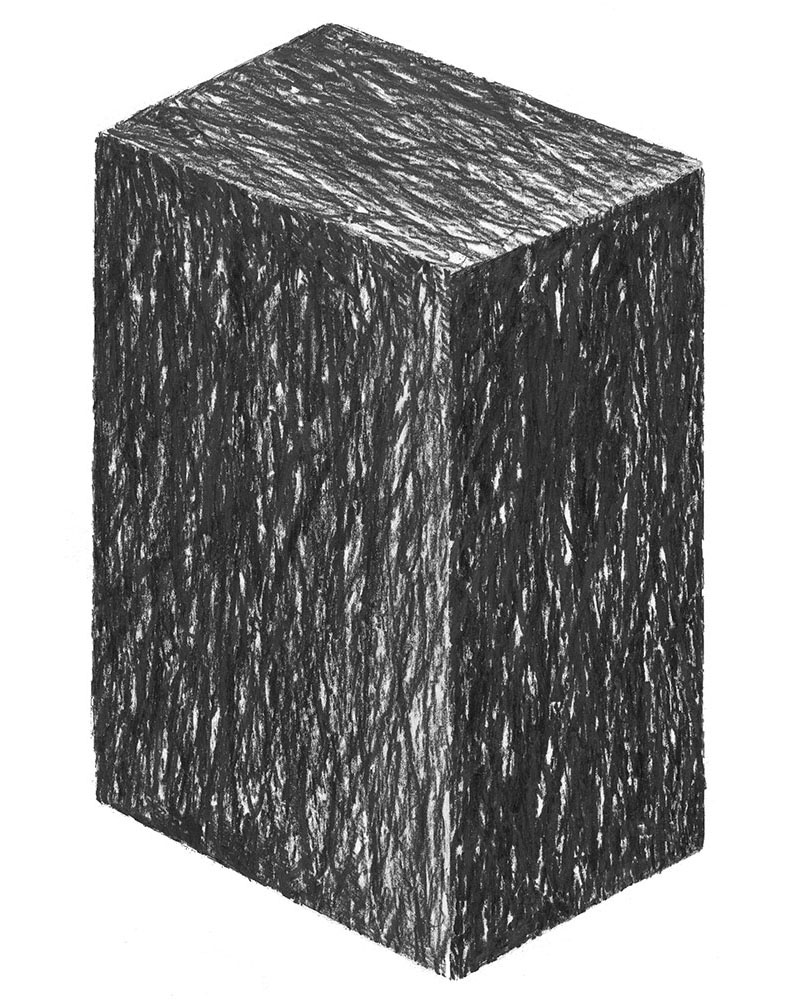

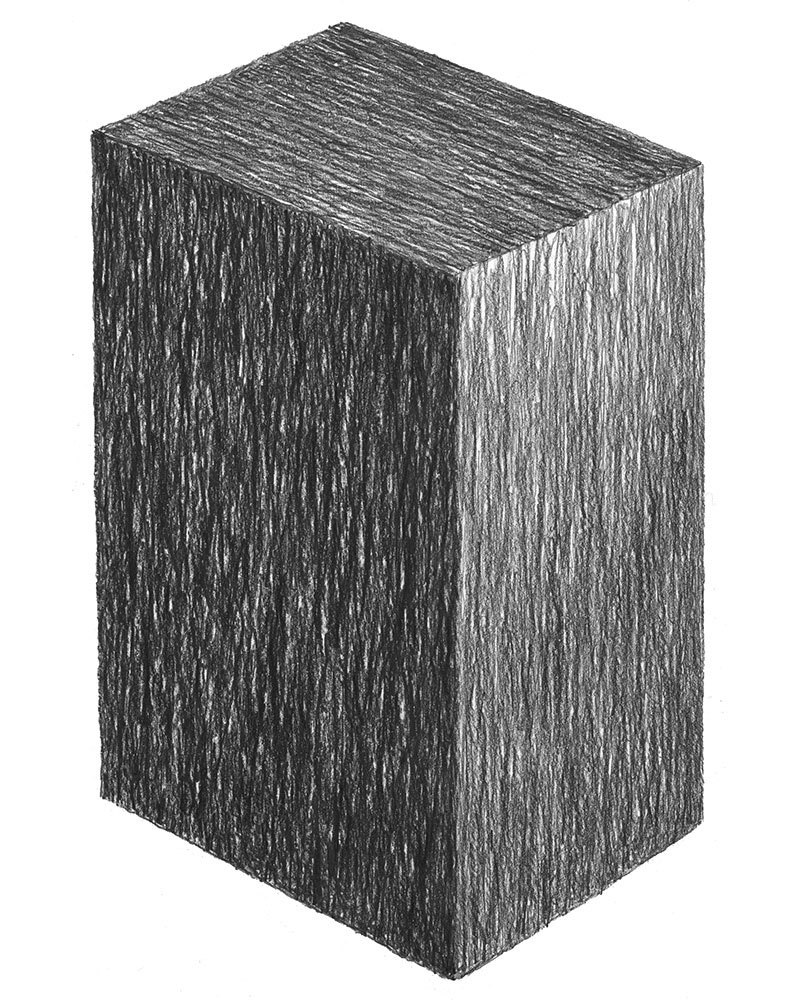

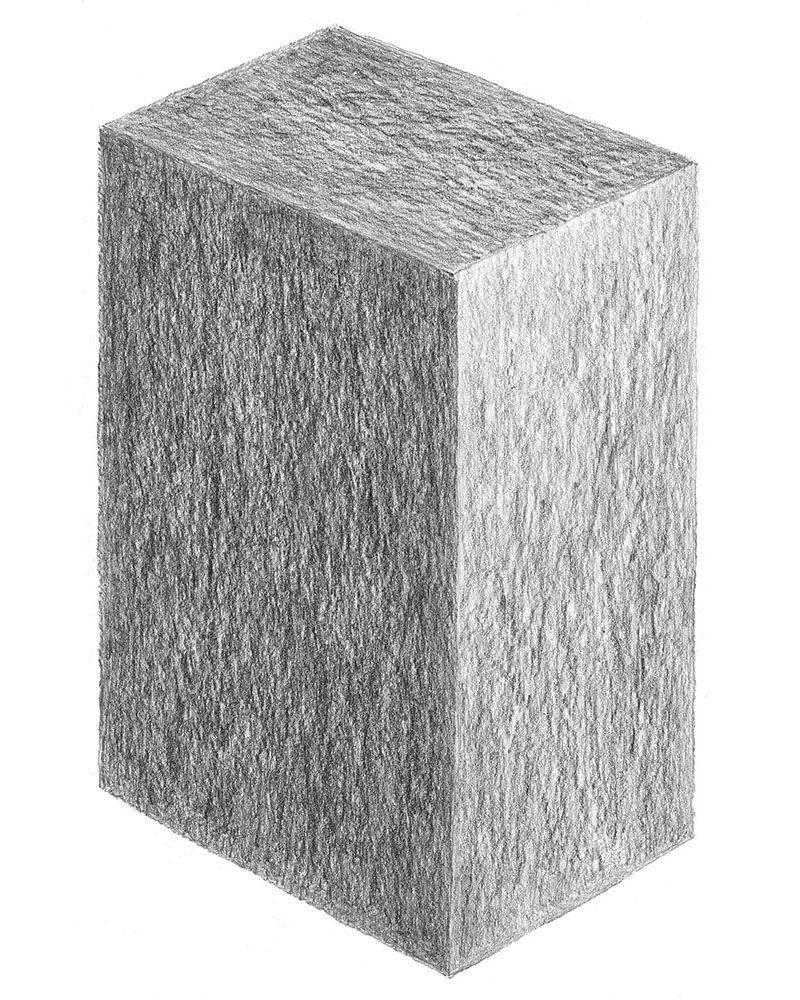

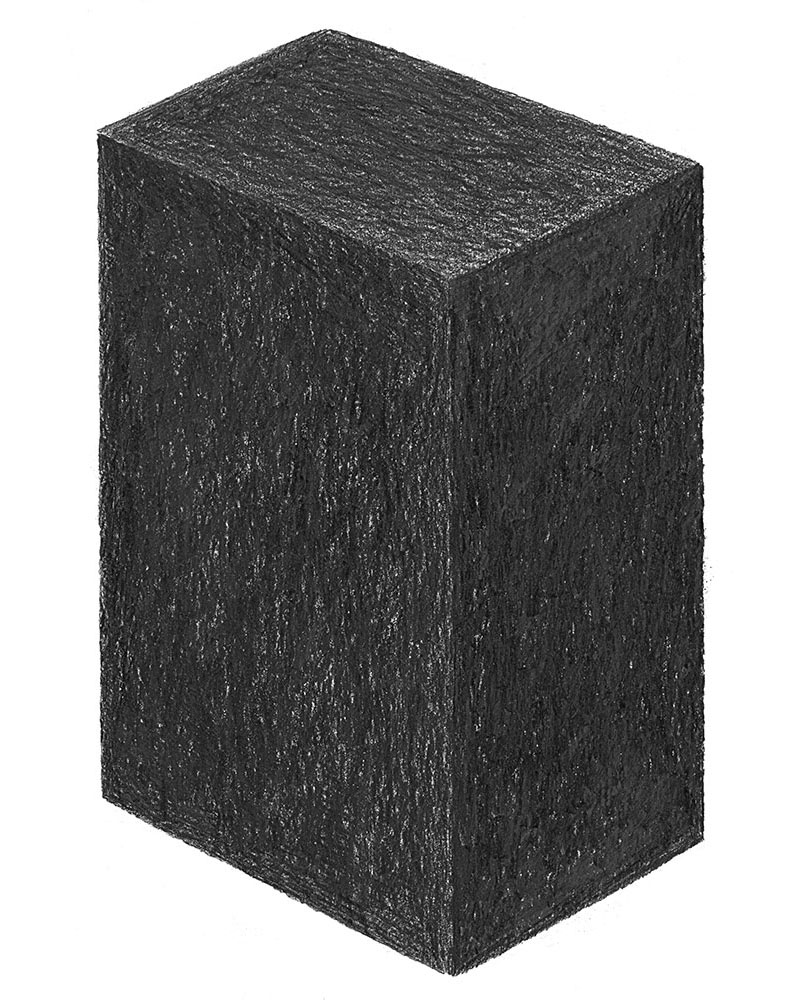

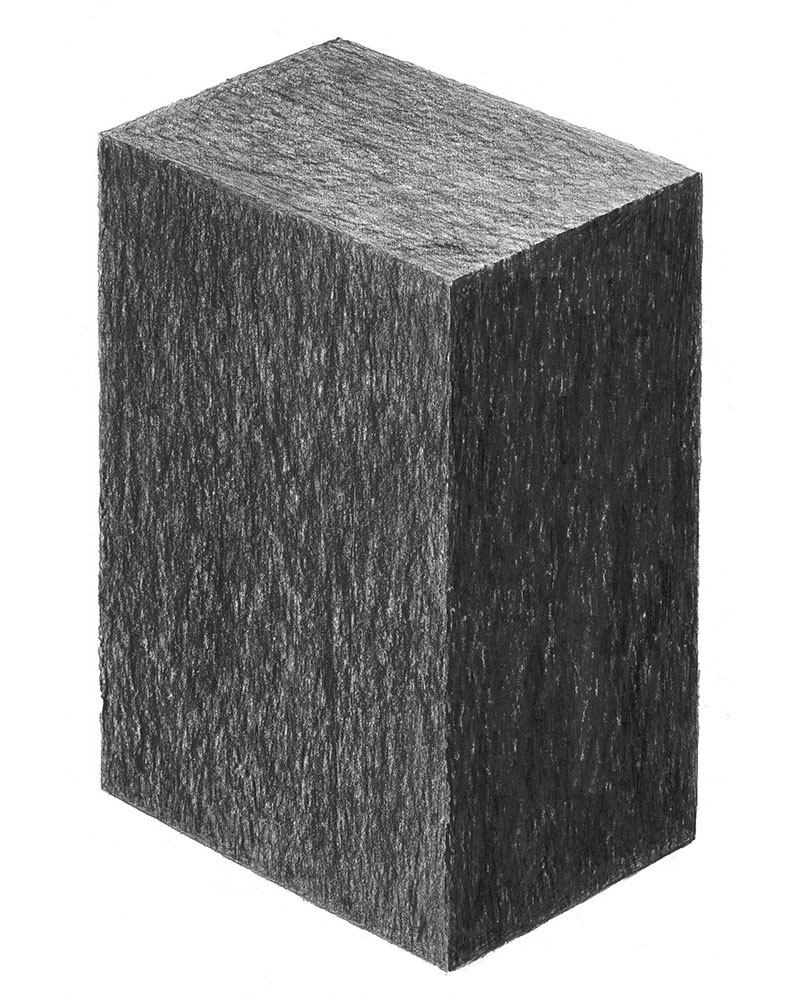

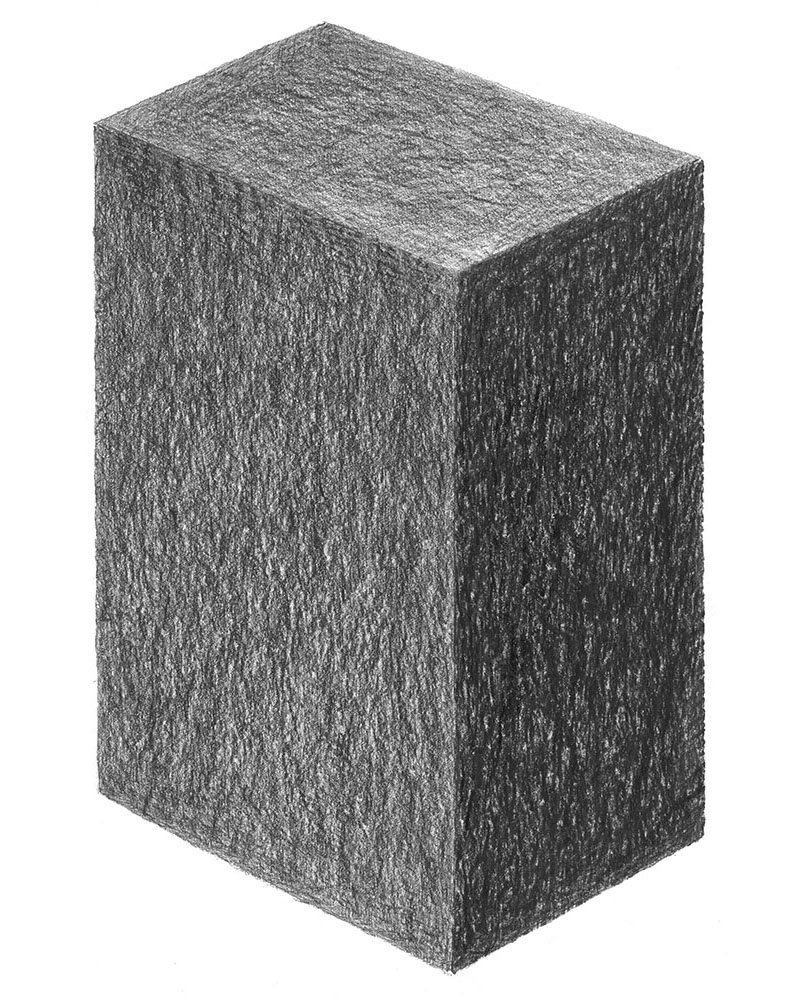

The monolith series can be set in parallel with the masks. The circular and elliptical monoliths are clearly stylized as faces and heads, while the blocks can be interpreted as spatial body shells. While the mask is primarily a means of revelation, these seemingly impenetrable circles and ellipses are reminiscent of shields, a means of concealment and protection. The simplicity and reductionism of the blocks, on the other hand, can evoke any box-like form that accompanies human existence, from the cradle to the bed to the coffin.

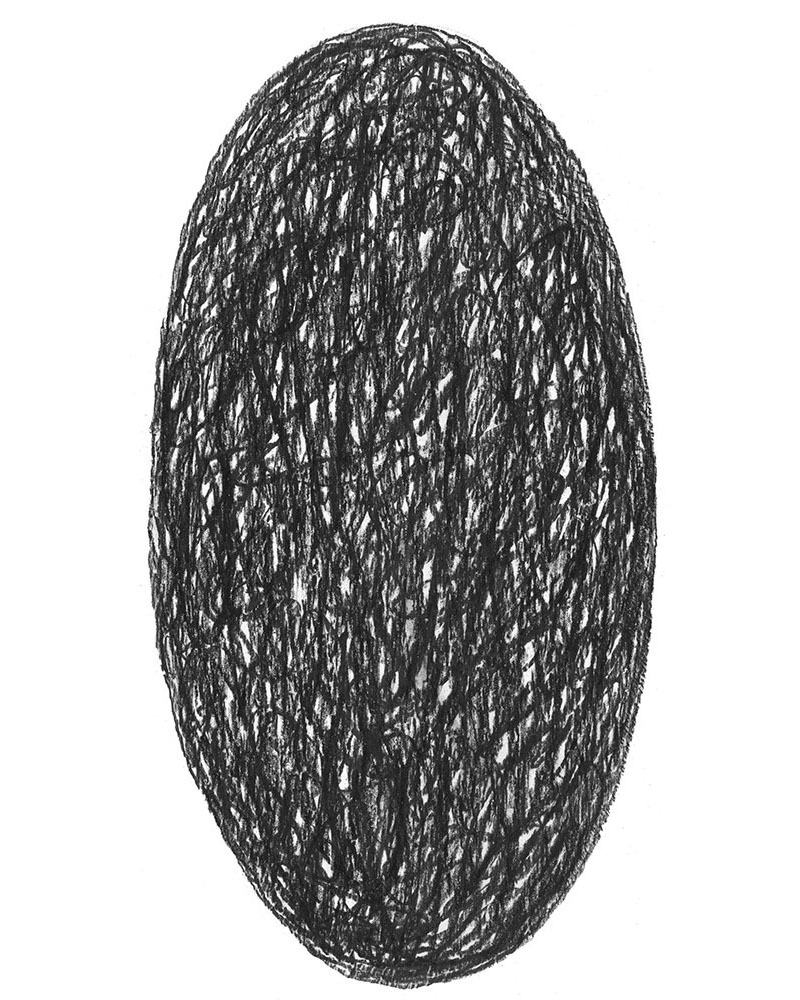

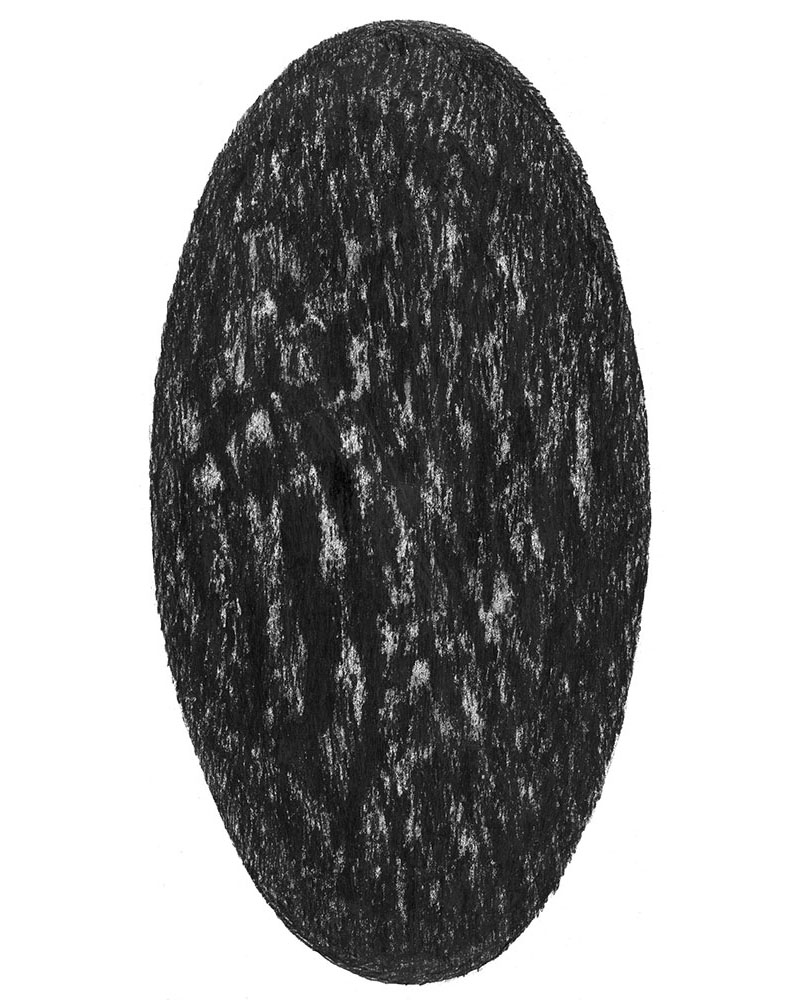

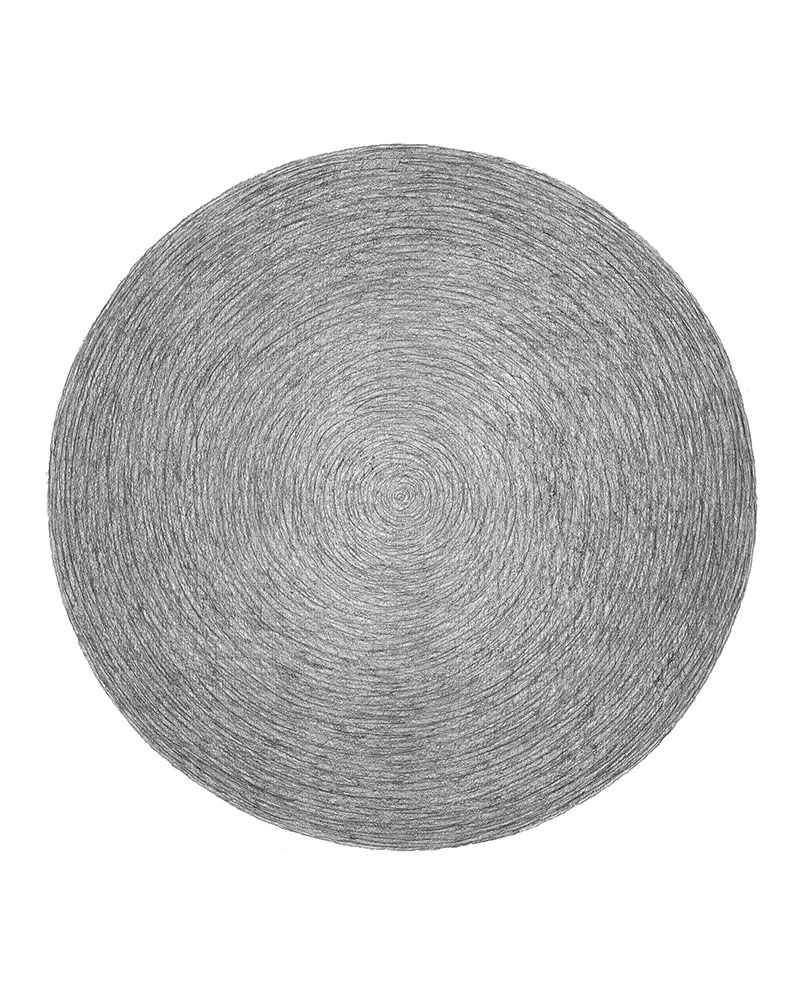

On the four-by-four panels, the monotonically repeating, regularly arranged geometric shapes of the same size and setting, that is, the circles, ellipses set on their longitudinal axis, and axonometrically depicted blocks are varied by different factorial solutions. The swirling motion on the surface of the circles is made perceptible by the concentric or spiral grooves. The geometric shape, in addition to being reminiscent of the human face, also recalls another organic form, the annual rings of woodcuts. The ellipses are sometimes interlaced with scratch-like pencil traces, sometimes covered with frottage-like tonal graphite etchings that resemble the surface of fossils. The longitudinal oval shapes also suggest another unique characteristic, as they evoke the association of enlarged fingerprints.

Through the technique used in the drawings, the chemical and physical properties of the material used give these works a philosophical message. Just as graphite and diamond represent the two extreme poles of bonding carbon atoms (graphite being the softest and diamond the hardest carbon allotrope), the geometric shapes (circles, ellipses, block shapes) of Győző Sárkány’s mask and monolith series polemicise with the organic surfaces formed by graphite.

Judit Szeifert art historian